1942: Dreizehnlinden / Papuan, Santa Catarina, Brazil

In the face of war abroad, Brazil’s President Vargas attempted to remain neutral. Brazil depended upon trading partnerships with both Germany and the United States, the manufacture and sale of arms to Germany making up a significant percentage of that trade. However, increasing cooperation and financial investment from the United States motivated Brazil to officially sever diplomatic relations with Germany, Japan, and Italy on January 28, 1942.

In July 1942, the press credited German U-Boats with sinking thirteen Brazilian merchant vessels in the South Atlantic. Others speculated that credit for the attacks belonged elsewhere. Regardless of the perpetrators, Vargas resisted further measures against the Axis. The Brazilian public, on the other hand, took to the streets to demand that the government retaliate with a declaration of war. In the capital of Rio de Janeiro, restless ne’er-do-wells exercised their frustration on German-owned restaurants and other businesses.

Still, the thousand-kilometre distance between Rio and Dreizehnlinden shielded Gisa, her family, and other German-speaking residents from any direct confrontation and the undercurrents of conflict continued to affect Gisa as only a vague, indescribable sense of discomfort. At age eight, she still more closely resembled a child several years younger, small and thin with too-large eyes. She quietly kept to corners and preferred to sit with her legs pulled tight to her chest and her arms around her knees, when allowed the option.

After school, Gisa tended to drop her books inside the front door and then disappear again without a sound. She would wander around Dreizehnlinden, sometimes people-watching through the open windows of the town’s stores. Often, she stopped to gaze up into the vacant windows of the tall red-brick tower of the Kleine Schloss, now devoid of its master. When encountering her fellow townspeople, whether superior or peer, she would scurry quietly away in another direction. Occasionally, she walked up into the hills to visit the cows. Her family left her to her own devises, as long as she returned in time for dinner, which she usually did, led by her appetite.

Then, in August 1942, definitive news reached the small town that a single German submarine, the U-507, had sunk five Brazilian vessels in two days, causing more than six hundred deaths. These new attacks, combined with diplomatic pressure plus economic incentives from the United States, finally led Vargas to declare war on the Axis on August 22, 1942, officially joining Brazil with the Allies. That’s when the war truly reached Dreizehnlinden, forever shifting its foundations.

In a show of pro-Brazilian nationalism and anti-German sentiment, Vargas immediately instituted a number of domestic sanctions. In one foul swoop, he banned use of the German language in public, expropriated German-speaking settlers’ lands, and demanded the renaming of Germanic place names with suitably Brazilian ones. Dreizehnlinden became Papuan. All around them, other German-speaking settlements endured the same treatment.

Wide-eyed, Gisa and her stunned schoolmates watched as Brazilian officials carted their German-language books outside to the schoolyard in a wheelbarrow, tossed them into a pile, and then set them ablaze, feeding the already greedy flames with Dreizehnlinden’s beautifully carved sign as a final offering to the Brazilian nationalist gods. Her sister, Teresa, arrived, along with other neighbours, enfolding her arms around Gisa’s trembling shoulders. The wind changed direction, assaulting Gisa’s eyes with smoke, until tears streamed down her blanched cheeks. Trial by fire.

Wide-eyed, Gisa and her stunned schoolmates watched as Brazilian officials carted their German-language books outside to the schoolyard in a wheelbarrow, tossed them into a pile, and then set them ablaze, feeding the already greedy flames with Dreizehnlinden’s beautifully carved sign as a final offering to the Brazilian nationalist gods. Her sister, Teresa, arrived, along with other neighbours, enfolding her arms around Gisa’s trembling shoulders. The wind changed direction, assaulting Gisa’s eyes with smoke, until tears streamed down her blanched cheeks. Trial by fire.

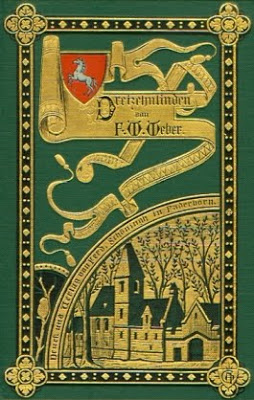

One of the bureaucrats approached the fire with one last armful of books and stopped to the right of Teresa and Gisa. Teresa’s eyes landed on an old green leather-bound volume with gold gilding and a red crest—the original epic poem by Fredrich Wilhelm Weber, entitled “Dreizehnlinden”, after which they had named their colony. The book had been sent from Austria as a gift for the new school.

As the man lifted the text with his left hand from the stack cradled in his right arm, Teresa stepped forward and grasped it. She locked eyes with the official with a look of half-defiance, half-entreaty, the book suspended between them. He paused, considering the consequences of his next move, then let go, saying “em casa só” (at home only). Teresa turned without a word, pulling Gisa protectively to her side and hastily escorted her and the book home, successfully salvaging a small piece of Dreizehnlinden’s history.

That night, Teresa, who shared a small back bedroom with Gisa, awoke suddenly to find Gisa’s side of the bed empty and cold. She whispered Gisa’s name and scanned the room. She searched the bathroom and kitchen. No Gisa. Panicking, she awoke her parents. Her father lit a lantern and they searched the house again. He noted the still-locked door but searched the yard regardless.

In desperation, they broke the night’s deep silence and called Gisa’s name aloud inside and out. Suddenly, a small movement caught Teresa’s eye through the open door into their room. She ran to the bed and dropped to her knees, peering under it. There, wrapped in a shawl on the bare floor, lay slender Gisa, bleary-eyed and confused.

When asked why she had crawled under the bed, Gisa responded “it feels safer there”, to which her mother matter-of-factly replied that it was not safe to sleep on the floor in Brazil with the spiders and the snakes, picked her up, returned her into her bed with her sister, and then promptly retreated to bed herself without another word.

But, night after night, Gisa’s sister would find her curled up under the bed rather than upon it. Finally, Teresa acquired some straw, sewed Gisa a small tick from an old wool blanket and slid it under the bed. Still unsatisfied, she opened the chest at the end of their bed and withdrew a white cotton-covered feather blanket. Intended for her dowry, she had diligently toiled for months to save feathers from their chickens and ducks to make this blanket for her future marital bed. But, she couldn’t bear to see Gisa lying on that hard floor any longer with only a shawl for cover and there were no other unused blankets left in the house. She half-slid under the bed herself to arrange the feather blanket folded in half over the straw tick, pushing it closer to the wall so her mother would not notice it. From then on, Gisa slept comfortably, safe in her little nest.

The Brazilian government replaced the school’s worn German schoolbooks with shiny new Portuguese ones and their familiar German-speaking teachers with native Portuguese-speakers. They even erected a new flimsy sign declaring the town as Papuan for all to see. With few other choices before them, the community endeavoured to adjust into this shifted reality.

Strangely, despite the shock and angst, these changes put Gisa on a more equal footing with her family and community: now, they must all become Little Brazilians.

Notes:

I found an interesting propaganda video produced by the United States about Brazil in World War II. You can see it by following the Related Post, Brazil at War.